In an Oceanliners Magazine exclusive, Mike Walsh, a former crewman on Britannic (1929), shares with us his memories of finding a job on the last of the White Star Line liners.

There is a great deal of interest in the ocean liners of yesterday. I don’t think those of us who sailed on these super ships ever thought that posterity would be so kind to us. Sure, we knew we were privileged; it simply never occurred to us that those less advantaged might envy or share our sentiments.

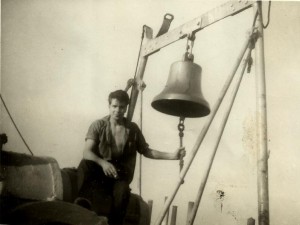

Mike Walsh, ringing Britannic’s focsle bell in New York during the summer of 1959. Britannic, the last White Star liner, was retired from service the following year.

Having completed my ten-weeks seamanship training at the Vindicatrix, a retired sailing ship moored at Sharpness on the Bristol Channel, I duly presented myself at the employment offices of the Shipping Federation in Liverpool. Situated at Mann Island, the building itself, whilst unremarkable in appearance, was placed at a pivotal point of all things related to the Maritime City’s history. This was considerable for the great “salty city” boasts many firsts. Only in one respect did Liverpool earn second place. The maritime port was once known as “The Second City of the Empire.” Only Liverpool and London, England’s capital city, possessed the maritime wherewithal to supply an empire so far-flung the sun never set on it.

To the rear of Mann Island are the oldest enclosed docks in the world. Canning and Salthouse Docks were both built in 1737. Opposite Mann Island is the Mission to Seamen. On the far corner, an imposing edifice colloquially known as the Bacon Butty (bacon sandwich) building. This on account of its brickwork alternating in layers between white and red. Officially this is Albion House, 30 James Street. Richard Norman Shaw, the architect of the White Star Shipping Company building, was the gentleman who designed and built Scotland Yard, the British Police Headquarters.

Just one hundred metres away, to the rear of Liverpool’s iconic waterfront, the buildings where Washington Irving, American author of the children/adults book Rip van Winkle in 1819, worked in a shipping office.

The White Star Building in Liverpool. Also known as “Albion House or” “30 James Street,” was constructed between 1896 and 1898. It served as White Star Line headquarters until 1934, when the company merged with rival Cunard Line.

Across the road from the Shipping Federation stand the Three Graces. These three beautiful buildings, that give Liverpool its distinctive waterfront, are firstly the Mersey Docks and Harbour Building. This edifice was built for an architectural contest then being waged for the best design for the projected Liverpool cathedral. Built in the Italian palace style, the architect’s submission had come second or third. Too good to waste, the blueprint design was afterwards used and soon to provide offices for those charged with the administration of what was then the longest and biggest docklands in the world.

Its neighbouring building in the centre is Cunard Building, home of the Cunard Shipping Company. The third building is the Royal Liver Building. The Royal Liver Building’s tower clock is far bigger than is Big Ben, the tower clock on London’s House of Commons.

In appearance the inside of the Shipping Federation was hardly different from any employment office. Inside were set about eight bank-like windows. At each desk a clerk whose responsibility was to allocate a ship to an unemployed seaman looking for a berth. In the room itself, seamen in groups huddled together as they spun their yarns, by which I don’t mean they were knitting jumpers. Little knowing what to expect, I, as as 15-year old Liverpool rookie deckboy, presented myself to a window where I handed my documents to the teller.

Smiling, the clerk rifled through a list set before him. Then, scribbling something on an A5 sized piece of paper, he passed the slip under the window in my direction. “Here, son. The Britannic is looking for deck-boys.”

Looking down Britannic’s Boat Deck. The liner’s iconic “White Star Buff” funnels gleam brightly in the sunlight, even as shadows lengthen on the deck below.

Taking the proffered slip I worked it out that I should immediately present myself to the bosun of the Cunard White Star liner, Britannic. Being a Liverpool lad, and as a consequence fascinated by all things maritime, I knew by heart all the great liners of the day. I needed little introduction to the sister ship of the White Star liner Georgic.

I never did attach much importance to the ship assigned to me as being the last of the iconic White Star liners. Nevertheless, it was a ship with an evocative background and an awesome heritage of ocean greyhounds. I took in my stride my knowing that my first ship’s colours and flags were the same as those of the Titanic, the Olympic; all those ocean greyhounds the names of which ending in ‘ic’.

Joining the Britannic, I was about to come face to face with one of life’s never to be forgotten experiences. With my kitbag slung over my young shoulders, I made my way along Liverpool’s Landing Stage through the security gates. The Pier Head landing stag is a floating harbor, the largest in the world. Strolling on down the stage I approached the liner now moored whilst waiting for its New York bound passengers. Many arrive at the city’s Lime Street Station half a mile distant. Here was the other end of New York’s Ellis Island: From the landing stage I was now treading, the United States, Canada, indeed much of the world, had been populated by the European Diaspora.

Despite my reputation as a descriptive writer nothing prepares one for the sensation of approaching on foot the mountainous superstructure of such a 27,000 ton super liner. It blots out the sun, the sky, it consumes you and it becomes your life. In my case, it was about to.

The Britannic bore the acronym RMS. This denotes the vessel as being privileged to carry Royal Mail letters and parcels to the United States. Under careful watch and extraordinary security, mail destined for the United States arrived from the Royal Mail Sorting Offices situated at the city’s Copperas Hill. Deep in the bowels of the leviathan special secure chambers for the Royal Mail and other products. These were usually distilled and subject to Her Majesty’s Customs and Excise. Unlike “lesser” ships of Britain’s Merchant and Royal Navies, from the mast of Britannic, the blue ensign gaily flutters. This denotes the ship as being semi-military in status. I seem to recall that a minimum of 10 percent of its deck crew, at one time or another, had served in Britain’s Royal Navy.

Taking one last glance over my shoulder, I took a deep breath. Then, like one of the children of the Pied Piper legend, I wandered up and into the cavernous interior of the RMS Britannic.