One of the worst maritime disasters in US Pacific coast history occurred on 4 November 1875.

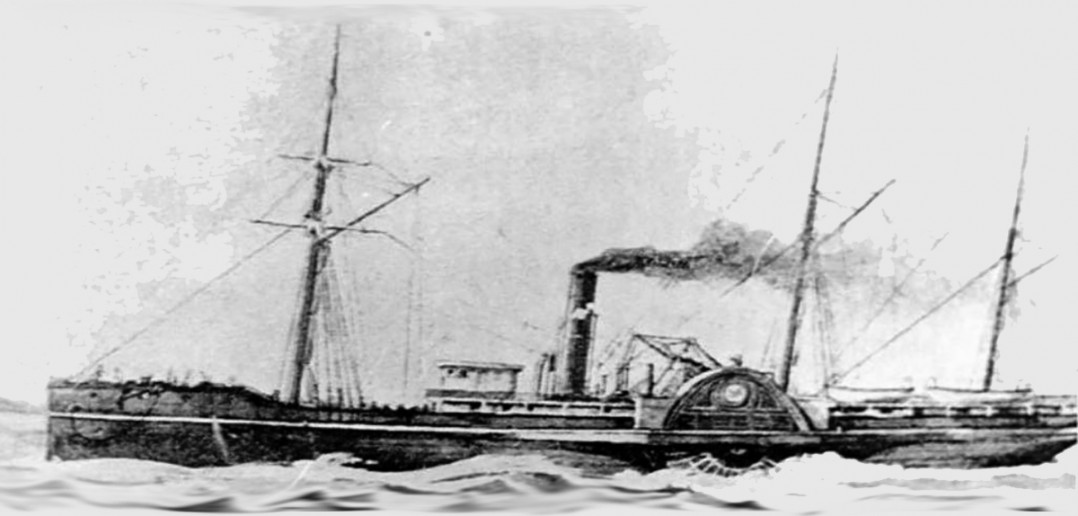

The sidewheeler Pacific (1851), en route to San Francisco from Victoria, British Columbia, with approximately 275 passengers and crew on board, collided with the sailing vessel Orpheus near Cape Flattery, Washington. Both vessels managed to continue on course, but Pacific foundered within 20 minutes and only two people survived. Orpheus’ captain—Charles A. Sawyer—who may have been drunk during the incident, later testified that he was unaware of the collision.

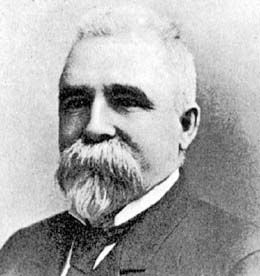

At the time of the incident, Pacific had only three crewmen on duty: an inexperienced third mate, an inexperienced helmsman and, a lone lookout. The overcrowded vessel, crammed with cargo and passengers (the exact number of people on board remains unknown), had been listing heavily to starboard, making steering difficult. To correct the list, Capt. Jefferson Davis Howell ordered two port-side lifeboats to be filled with water. Pacific was also running without port and starboard lights; only her white masthead light was visible.

Jefferson Davis Howell, Pacific’s captain, died in the disaster. His wife, who was also on board Pacific, died too.

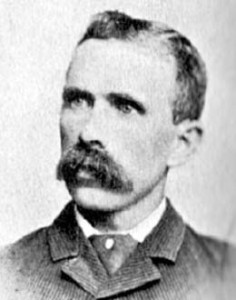

At 9:30 p.m., Orpheus’ Capt. Sawyer left the bridge in charge of second mate James G. Allen. A short time later, Allen reported the Tatoosh Island light off the port bow, but Sawyer decided it was an approaching vessel and ordered his ship turned hard to port to keep out it its way. The abrupt maneuver left Orpheus almost dead in the water. Capt. Sawyer could only watch as the other ship closed in without altering course. At the last minute, the steamship frantically blew her whistle and reversed her engines, but struck the Orpheus a glancing blow on her starboard side. The steamer then ran against the sailing vessel two more times, staving in side planks, breaking 40 feet of rail and carrying away the chain plates and most of the rigging on her starboard side.

On Pacific, Capt. Howell rushed to the bridge. He saw the running lights of a sailing vessel off the starboard beam drifting slowly away and realized there had been a collision. It was soon evident that Pacific was taking on water rapidly. She was, in fact, sinking. Passengers began arriving on deck to see what had happened, creating a chaotic scene.

With only a few lifeboats usable, most of Pacific’s passengers and crew soon found themselves in the cold ocean clinging to bits of wreckage. Most died quickly from hypothermia. One passenger survived by hanging onto the ship’s wheelhouse. The only other survivor was a crewman who was rescued by the United States customs ship Oliver Walcott.

The next day, Orpheus’ Capt. Sawyer mistook the Cape Beal lighthouse on Vancouver Island for the beacon on Tatoosh Island and ran his vessel aground in Barkley Sound. There were no casualties, but the ship was a total loss. The same might also be said for her captain.

The Captain of the Orpheus, which collided with and sank the steamer PACIFIC, will have to rise and explain that transaction more favorably for himself, or receive the condemnation of the civilized world for his behavior on the occasion of the disaster. The latest accounts place him in a very unpleasant position, and one from which it will be difficult for him to extricate himself. One of the seamen of the Orpheus, named CHARLES THOMPSON, has made a sworn statement before a Notary Public which charges the Captain of that ship with having been the cause of the disaster. He says that on raising the lights of the Pacific, he was ordered by the second mate to head for it, and a few minutes after the Captain came on deck and ordered him to again put the ship on her course, and about three minutes afterward he was ordered by the Captain to let her luff, which he did. After this the Captain signified his intention to speak the steamer, for which purpose the light was kept dead ahead, until the two vessels collided. Then the steamer followed the ship, the people on board shouting and calling on the captain of the Orpheus to stop, and rescue them, but he did not heed the cries, kept on his course, and the steamer was soon lost to view.

—Oakland (California) Tribune, 24 November 1875

Please help keep Ocean Liners Magazine afloat. Any amount will be greatly appreciated.

—Regards, John Edwards, Editor/Publisher.